“The music of the future will not entertain,

It's only meant to repress and neutralize your brain ”

The formerly angst-ridden, now relaxed free thinkers that comprise the majority of Porcupine Tree’s Indian fanbase might view these lyrics as a meditation on the homogeneity and numbing effect of modern music and music to come, a concept Steven Wilson has always prophesized about and leant into even more on future projects. The word (and indeed, the song) speaks of a genre of music that is rooted in the past; the result of a weird psychological experiment that started out as a project connected to the US military, no less.

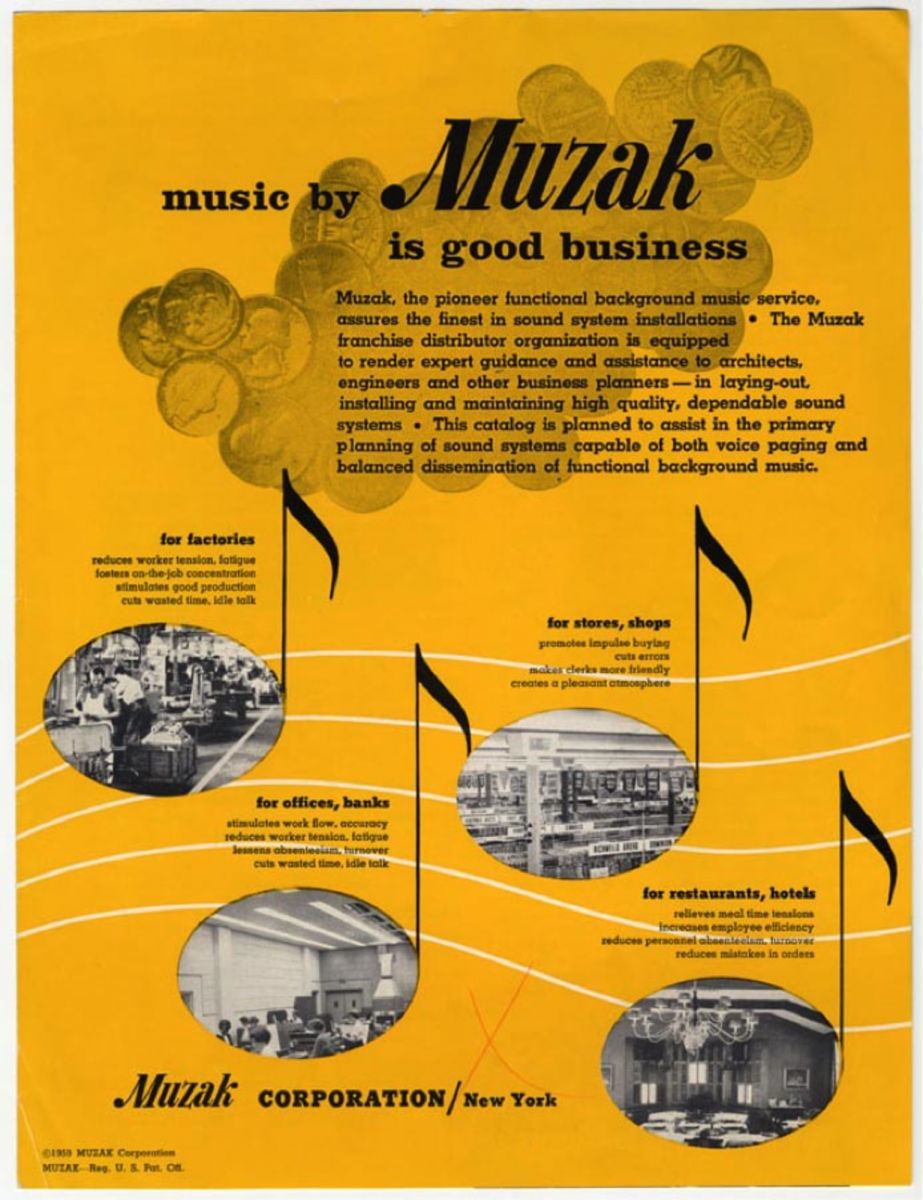

Muzak is the name given to the music that is played in public places like hotel lobbies, businesses, high-end air-conditioned waiting rooms, and you guessed it, elevators. All those bland instrumentals you have heard while going to the tenth floor of your workplace, waiting for your buffet breakfast on a vacation or standing in a mall queue to avail an offer on hand-washed denims, legally comes under (or more accurately, used to come under) Muzak. The idea of supplying music to be played in public spaces started in the 1920s with Major General George Owen Squier, an inventor who worked as a signal officer for the US Army (he also invented multiplexing, a way to make telephone networking easier). He came up with an idea to provide music to people’s homes for free via their phone lines because radio was too expensive for households to afford at the time. He named his venture Muzak (a play on the equally made-up word ‘Kodak’). The listeners were charged on their power bill; his primitive streaming service was very popular until the 1930s when home radio became cheap and people could listen to wirelessly transmitted music for free (supported by ads, of course) . It was then that Muzak was purchased by a private party (an entrepreneur named William Benton representing none other than Warner Bros) who decided to send music to businesses and other establishments to maintain profits. This is where the story gets a little weird.

Once Muzak was sure of its audience, they embarked on an experiment that they thought would change workspaces forever; something they called ‘Stimulus Progression’. They played music composed specifically to make workers more productive. The songs had no lyrics (they were convinced vocals would be a distraction) and were broadcast as fifteen-minute long pieces. All the music was played by Muzak’s own set of locally-recruited musicians and was broadcast with fifteen-minute gaps between songs; the company believed that such periods of silence prevented fatigue. The pieces were composed such that they grew in tempo as they progressed; supposedly to subconsciously make employees work faster in time with what they heard.

This idea of using music to increase efficiency and decrease tiredness prompted a major backlash from the general public, who protested the project’s intent of manipulating behaviour and productivity. Claims of brainwashing were widely levelled at Muzak but in spite of this, it remained popular for the next decade; it was reportedly used in the White House and by NASA to increase the work rate of their employees.

In the 60s and onwards, much music became the focus of the youth and people who considered it a way to rebel; as a consequence, Muzak lost its popularity among the masses. Their response to this was to include lyrics and popular music in their transmissions, but it was too late to fight against the rock and punk craze; the company was reduced to sending music to barbershops and other small establishments. Other companies had also started their own original music programming which quickly ran Muzak out of business. By the 70s and 80s, Muzak had been overrun by players who provided services that were far more specific, down to language and genre-specific music like Latin for Mexican and Spanish restaurants. Even so-called ‘easy listening’ music was provided for general use. Brian Eno made an album in 1978 called ‘Music For Airports’ that he said was intended to deconstruct and improve the Muzak genre; something that was intended to promote free thought instead of controlling and thus limiting it. This album is regarded to be the genesis of a genre we all know today: ambient. It’s notable that Muzak as a concept never lost any steam despite the allegations levelled against it. It became the sonic status quo for background music in semi-public and public spaces, and remains so to this day.

Muzak’s portfolio underwent a sea change towards the turn of the millennium; they shifted from original programming to making customized playlists for particular brands and shopping chains. They started to concern themselves with finding which pop hit went with which clothing line, among other trend-based musical experiments. However, the old concept lived on in a few countries like Japan, where original music was still presented to customers.

In the late 2000s, Muzak Holdings (the company that started it all) ceased to be an enterprise and filed for bankruptcy to settle their debts. After a few legal incidents, it was bought by a company called Mood Media, which controls the licensing of public music and its distribution to this day. It has offices all around the world (yes, including India) and its permission and licensing is ‘technically’ required to play some music in your establishment. But its present state is irrelevant. What is important is the concept of Muzak and how it still affects us today.

Music has always been associated with freedom and the ability to subjectively take whatever feeling and thought one wants from a piece of art. The idea of a group of people using music to influence human thought and consciousness is not new in any way (one could argue that certain types of music are made for precisely that), but what is worrying is that eighty years ago, somebody realised that large groups of people can be influenced to work better and faster if you supply the correct background audio; to make more money. It is uncomfortable to admit that music, traditionally one of the last bastions of truth and pure art, can easily be used to influence people to do something they do not necessarily want to in an unnatural manner to maximise profits. Hopefully that is not the case today, given the amount of diversity and choice that exists in easily accessible popular culture. Please listen to whatever you want to. But think about this when you’re between the tenth and the eleventh floor in the lift on the way to your office job (or apartment building now that we’re in our current hellscape of the present day) and you hear saxophone or bland, non-intrusive lounge music. It’s wasn’t always for your entertainment.

Previous Article Interview With Tenma From Tamil Nadu Ensemble Casteless Collective Interview With Tenma From Tamil Nadu Ensemble Casteless Collective

|

Next Article Bhavi Chandiramani Is Forging Her Own Path With Moj Bhavi Chandiramani Is Forging Her Own Path With Moj

|

The group of musicians is acting as an extremely important bridge between contemporary presentation and shedding light on casteism and social issues we ignore all too often

Debojyoti Nath left his life behind to do a two-year journey busking in every state in the country. Then he decided to put out an album. That’s a lot.

The bassist talks about his father Eddie, future music and musical journey

Leave a comment